The debate surrounding the use of gender quotas to improve gender equality occurs often. Are they necessary? Do they work? When should they be introduced?

In answer to are they necessary, consider the below findings by the World Economic Forum in their Global Gender Gap Report 2020:

- It will take an average of 99.5 years, across 107 counties, to close the gender gap.

- To close the gender gap in political representation, it will take almost 95 years.

- Only 25% of parliamentary positions globally are secured by women.

- The economic participation gender gap will take 257 years to close.

Take a moment to reflect on these figures and then ask yourself if quotas are necessary. Well, I say they are required, and they need to be implemented now if we are to make progress on the above estimates.

A consistent thread in my studies this year is that women are underrepresented in decision-making and leadership positions (clearly supported by the statistics above). The basis for introducing a quota is to promote gender equality and inclusion.

A gender bias exists, whether it is conscious or unconscious, when nominating individuals to leadership positions. Those in power tend to appoint those that reflect themselves (termed affinity bias). A practical way to address this bias is to apply a gender perspective by acknowledging the bias and actively targeting diverse individuals by setting a target for increased female participation.

Without a quota or target to work towards how do we reach gender parity, and how do we ensure the representation of minority groups?

Gender quotas are internationally recognised due to their inclusion in the:

- Convention of the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW); and

- Women, Peace and Security (WPS) Agenda.

Critical mass: a fundamental ingredient

Krook (2015) notes that an element of quota campaigns is critical mass. The essential premise of critical mass is that to have a material impact; there needs to be a larger quantum of female participants in decision-making positions.

Research indicates that when women are provided with an opportunity to participate in leadership positions, this will lead to women’s interests being addressed. Listening to Women are the Business Podcast (episode 4), a guest speaker, Dr Sojo, argued for clear processes to increase women in politics. More women were essential as the needs of women and children were being ignored when policies were being developed. Dr Sojo provided the example that the reason many policies surrounding women’s reproductive rights exist today is due to women advocating for them.

A further example is the suffragette movement of the 20th century. This female activist group campaigned for the right for women to participate in democracy and their right to vote in public elections. Without these groups advocating for women’s rights, it would likely have taken longer for these laws to change, if at all.

It’s a human right

Women, as do all people, have the right to be heard and have their say on issues that affect them and their community. Men have long dominated positions of power. Women are consistently overlooked for equal representation in political parties, management positions, and in male-dominated roles.

And, to state the obvious, females make up 50% of the population. Hence, it stands to reason that they should be equally represented in decision-making positions and, ethically, it’s the right thing to do.

Quotas in the community

My studies have exposed me to the use of gender targets in a broad range of social and political circumstances, including participation in peacemaking negotiations, as members of government, and peacekeeping operations.

The UN, in recognition of the disproportionate effect conflict has on women and children, adopted Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000) to emphasise the importance of women’s involvement in the peacebuilding and peacekeeping process. There have been a further nine resolutions following this all building on women’s inclusion.

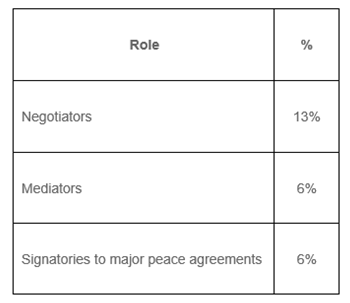

Data collected by the UN shows that women participating in the peace negotiations increase the chance of the peace agreement lasting 15 years by 35%. Yet, between 1992 and 2019, the number of women involved in peace negotiations were:

You must wonder if the evidence supports the link between long term peace with female participation, why are these rates so low? Gender stereotypes and cultural practices may be contributing to this.

Stereotypes suggest that people in powerful positions typically have masculine qualities. They’re strong, assertive, and influential; qualities that are not traditionally associated with women.

Feron states in her policy report, that when peace is being negotiated, it is being performed at a fast pace and participants are gathered from the military and political groups leading the conflict, resulting in more men being involved. Again, both these groups are male-dominated, so it is unsurprising this flows to the negotiation table.

Emerging research has also found that increasing the number of female peacekeepers in peacekeeping operations enhances their operational effectiveness. While researching the impact of female peacekeepers in Liberia (UNMIL), empirical evidence suggests the presence of female peacekeepers, assisted in the reduction of sexual and gender-based violence. [1] UNMIL has been hailed a success by the UN, in part due to the first all-female formed police unit being sent from India to participate. Evidence supports the benefits women play in being included in leadership positions. Their involvement is linked to more sustained peaceful societies.

Quotas on company boards

Gender diversity has expanded from a social and political right to a corporate governance issue for businesses (de Plessis. 2015).

Corporations worldwide have been targeting 30% of women on their boards. The 30% Club, originating in the UK in 2010, is a global campaign that engages with listed companies and promotes a gender balance not only on boards but throughout the organisation.

Supporters recognise that the inclusion of women and people from diverse backgrounds on boards is good for business, both from a profitability standpoint but also from a social responsibility position.

A report released by the Workplace Gender Equality Agency and the Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre found a link between increasing female participation in leadership positions with the increase of business productivity and profitability.

- An increase of 10% of women in key leadership roles equates to an increased average market value of 6.6% or $105 million.

- Appointing a female CEO results in a 5% increase, which is almost $80 million for the average ASX200 business.

So, for people who still believe diverse boards are not necessary – then perhaps the opportunity to outperform competitors with little female participation (and likely more money in the pockets of employees and shareholders) will convince you.

Shouldn’t appointments be merit-based?

An argument made against a quota is that of merit. Individuals should be appointed based on their ability to do the job or the skills they bring to the table.

Businesses and organisations want the most qualified person for the role so that the organisation’s strategy is achieved. One flaw with this argument is that privilege and the existence of an uneven playing ground is not recognised. Everyone has not been afforded the same experiences in life. People may have limited access to wealth, education, health, and security. Individual circumstance needs to be a consideration when determining a person’s ability to fulfil a role. They may not have an expensive MBA, but they may have lived experience or experience at a grassroots level.

Token appointments and meaningful representation

The promotion of women to senior positions cannot be a case of a token appointment to meet a target. Women need to be given the authority and power to act in the capacity in which they are appointed.

While researching the inclusion of women in decision-making positions following Timor Leste’s independence, I read several articles on their progress in gender equality. Recognising the need for women to be involved in the peacebuilding process, women were included in the 2001 Constitutional Assembly and a gender quota introduced in the 2007 National Election Law. While these are accomplishments furthering gender equality, Niner (2017) noted that the women who occupy these positions were considered part of the elite in Timor-Leste[2]. As 70% of Timor-Leste’s population is rural-based, it is questionable as to whether this is an accurate reflection of the community.

To understand the community and the challenges faced by different groups, leaders need to reflect the diversity of the community in which they serve.

Beyond gender quotas

Governments, groups, and businesses should be representative of society and the community in which it operates. Quotas for participation has evolved and is now also being used to promote intersectionality and diversity in general. To be representative of the community means more than just including women. It means looking at intersectionality and having people from different ethnic backgrounds, those with disabilities, the LGBTIQ community, and multiple age groups.

California has gone one step further to introduce intersectionality following the legislating of minimum female board members. In September they passed a law which requires publicly listed Californian companies to diversify their board by at least one member from an underrepresented community by the end of 2021 and two to three members by the end of 2022.

Final thoughts

In summary, there exists a need for improved gender representation and inclusion in decision-making positions and policymaking. The inclusion of a diverse range of individuals in these positions results in creating a more equitable environment for everyone. The increased representation of women is relevant, and crucial, in all of society, from combating climate change, the recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, through to optimising business performance and profitability.

Businesses and governments have had ample opportunity to address gender equality. However, due to the patriarchal structure of society, there needs to be a system that mandates women’s involvement in an influential and meaningful capacity. Preferably gender quotas should not exist in isolation, quotas should be used in conjunction with principles and activities that challenge gender norms and stereotypes.

If we are serious about gender equality and giving minority groups a voice, then gender-based targets are a vital component in achieving this goal.

[1] Pruitt, Lesley J. The Women in Blue Helmets: Gender, Policing, and the UN’s First All-Female Peacekeeping Unit. Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2016. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1c6v9f6.

[2] Editor, S. Niner. 2017. Women and the Politics of Gender in Post-Conflict Timor-Leste: Between Heaven and Earth. Oxon and New York. Routledge.